Ordering takeout has revolutionized China’s dining scene, but what is the real price of food deliveries and can it last?

Go to any restaurant in China around meal time and you’ll find blue, red and yellow-clad food delivery riders often outnumbering the diners. It is a trend that has benefited everyone who likes to eat at home, but is causing chaos on the roads and also creating major losses for the companies trying to make money delivering takeout foods.

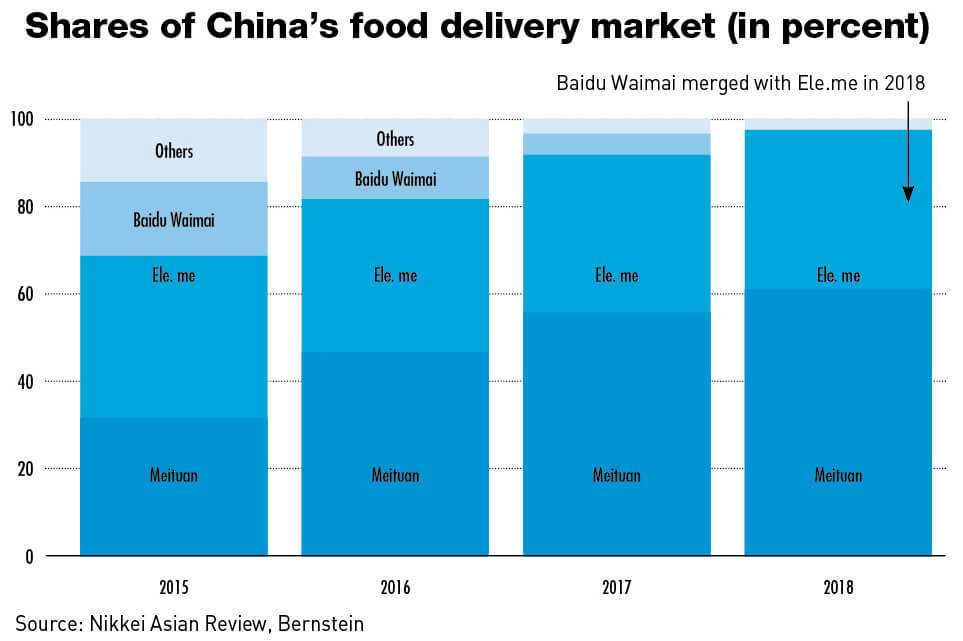

Food delivery has become a cornerstone of city life in China over the last decade. The number of delivery businesses initially mushroomed and then faced off in an intense battle for market share that has left only a handful of significant players still standing, most notably Ele.me—controlled by online retail giant Alibaba—and Meituan Dianping, whose largest shareholder is Alibaba’s top rival, Tencent.

Ele.me (pronounced UH-luh-ma, which literally means, ‘are you hungry?’) employs 15 thousand staff and delivers more than 9 million orders daily.

Meituan is larger, delivering not only food but other consumer products. It has surged from providing 1.7 million deliveries in 2015 to 11.2 million deliveries in 2017.

But both companies are still losing money.

“They have improved the efficiency of getting food for digital natives,” says Xue Yu, research manager for the internet and blockchain at IDC. “But it seems like the war between Alibaba and Meituan will continue for a long time.”

He says China’s online food delivery business was valued in 2017 at $32 billion with registered users numbering 300 million, up from 110 million in 2013, and with 80 million active users monthly.

Meituan last year raised $4.2 billion in an initial public offering (IPO) on the Hong Kong stock market, valuing the company at $52.8 billion. It was the world’s largest internet-focused IPO for the past four years, but the company’s share price has struggled. Meituan’s third quarter figures released in November showed both a tripling of its operating loss, and a slowing in market growth compared to the first half of 2018.

The key element for the industry is the mobile phone applications that each food delivery platform operates. Easily downloadable, each app lists restaurants in the user’s vicinity that take orders for delivery. Within seconds after an order is placed, the restaurant begins preparing the order for the delivery rider to collect and rush to the customer, usually on an electric bike, within an agreed time. The entire process can be monitored by the diner-to-be on the app, with details including the delivery driver’s name, phone number and real-time location. Ele.me counts 1.3 million registered merchants spread across 2,000 urban areas while Meituan has 7 million merchants in 2,800 cities.

Despite the efficiency of the app, the financial foundations for the instant food delivery business in China are far from solid. Players in the waimai industry, as the food delivery business is known, are using a combination of innovation and discounts to keep afloat.

In January, Meituan received the International Innovation Enterprise Brand Award for its work with distribution robots and in February it was named the world’s most innovative company by Fast Magazine in its annual ranking of the 50 top companies around the world ‡ the first time a non-US company had claimed the number one spot. But it is the discounts that are hurting the companies most.

Meals on Wheels

“Ultra-convenience and—until recently—heavy subsidies are the rocket fuel which have driven China’s on-demand food delivery market,” says Michael Norris, strategy and research manager at AgencyChina, a China-focused marketing and sales agency.

The delivery companies initially charged the restaurants nothing to get them to join their networks, and also provide other benefits such as cheap advertising to keep them involved. On the consumer side, discounted pricing is used to lure customers. Meituan revealed that it spent RMB 4.2 billion ($626 million) on discounts in 2017, and in an effort to boost market share, Alibaba pumped in RMB 1 billion every month into Ele.me from July to September last year. Meituan now has about 63% market share, while Ele.me is at 35%, according to a report published by Beijing-based 3rd-party market researcher DCCI.

“Last year, one hotspot for competition between Meituan and Ele.me—Wuxi, a city just west of Shanghai—saw meals subsidized to the point of effectively being free,” says Norris.

Competition between Meituan and Ele.me has become so fierce that customers now say that their services are similar to the point of it not making a difference who they order food delivery from. “I order meals from Ele.me once to twice a week,” says Xu Shanshan, an officer worker in Shanghai, “I don’t find there to be much of a difference between what Meituan and Ele.me offer.”

In 2017, the average order value on Meituan was RMB 40 but that is usually not for just one person. Most office workers spend in the region of RMB20-25 to order their lunch using the apps, and discounts play a big role. “If it was expensive I would not order it,” says Liu Jie, a white-collar worker in Shanghai, who regularly uses Meituan.

Everyone is gaining from the discount war, except for the delivery companies themselves. “Certainly the main beneficiary is the customer, but the restaurants and the delivery riders also benefit from this,” says Xue. “Restaurants can gain more customers, and riders can get a job with good pay—both get money.”

Delivering Profits

Baidu, the third of China’s internet giants after Alibaba and Tencent, originally had its own player in the game, Baidu Waimai, but sold the business to Ele.me in 2017. The car ride hailing business Didi Chuxing attempted to enter the market in 2018, and Meituan retaliated by entering the car ride hailing business. They then agreed to a truce.

“Didi and Meituan aggressively dipped their toes in each other’s core business last year, but seemed to have reached a truce. Didi isn’t planning to invest further in food delivery, and Meituan isn’t eyeing up ride-hailing markets beyond Shanghai and Nanjing,” says Norris.

Meituan in particular has come under intense scrutiny over its profitability since its IPO. In its accounts for 2017, the company showed an 8.1% gross profit margin for its food delivery business, but that was only part of the picture. The biggest cost shown was payments to delivery riders, but what was not included were the costs of obtaining the sales in the first place. Meituan does not break down its selling and marketing expenses and so it is impossible to know how much it specifically dedicated to food delivery, Marketing and sales was the company’s largest other cost in 2017 and is one of the main contributions to the company’s operating loss. “That loss widened over the [2018 third] quarter, which spooked investors,” says Norris.

The company consists of three business units: food delivery, hotel and travel, and what it describes as “new initiatives.” New initiatives include Mobike which Meituan purchased in 2018 and a number of other non-food delivery merchant solutions. “Meituan’s ‘new business initiatives’ is where they are bleeding lots of cash,” says Norris.

Like any business, Meituan and Ele.me have two options to deliver profitability—increase revenues or reduce costs. But it is getting tougher to deliver either. The apps are trying to get more money out of restaurants and reduce the amounts spent on delivery riders—anything to avoid raising prices to the consumer.

In China’s major cities, the companies now typically charge restaurants a commission for each delivery, of around 18-20% in Shanghai—a similar level to the amount charged by food delivery companies in the US.

For the delivery rider brigade, rates have been cut and now start at just RMB 3.6 per delivery. The average target time for a delivery has also been reduced from 40 to 36 minutes; meanwhile fines for late delivery have increased.

“For many young unskilled workers, food delivery seems like a good option to make a decent income and work on their own schedule but it is a very high pressure job and if they are involved in an accident they might be out of work for months on end and have substantial medical bills or even have to pay compensation to a third party if they were deemed to be at fault in an accident,” says Geoff Crothall, communications director of the China Labour Bulletin.

Increased prices for consumers is the toughest option. Savvy consumers can click on this app or on that app to get the best deal, and Ele.me and Meituan know that raising prices will likely push costumers to defect to the other app. “It’s trying to strike a delicate balance between commissions, delivery fees, driver efficiency and platform subsidies,” says Norris.

He says that in tier-one cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, it is already nearing the inflection point where it is cheaper to eat out than in.

Riders On the Storm

The waimai business depends on speedy delivery, meaning that riders often have to take risks to deliver on time. The result, inevitably, has been disregard for traffic regulations and a large number of accidents, sometimes fatal. Figures from Nanjing reported by the People’s Daily in September 2017, said that food delivery riders are involved in 90% of all traffic accidents, while in Shanghai there is a fatal accident involving a delivery driver every 2.5 days, according to statistics given by the Worker’s Daily.

“In the event of injuries, or even deaths, no one seems to take corporate responsibility because there is “no boss” who can be held legally accountable,” says Jenny Chan, assistant professor at the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Chan notes that most delivery workers are classified as independent contractors rather than employees.

China Labour Bulletin reported that there were 15 known cases of strikes by food delivery workers over the summer of 2018 alone. “I think it is fair to say that for many workers conditions are not improving,” says Crothall. “However, there is some evidence that the delivery companies were willing to make some concessions after workers staged protests. That said, the basic business model seems to be the same and workers are still at the mercy of arbitrary and unilateral management decisions.”

Despite the obvious risks of the job, young workers are still attracted by the opportunity because if you work hard you can earn a good income, and payments from the companies are reliable and quick. “It is true that money can be made quickly by delivering food and drinks every day and every night,” says Chan. And, she says, delivery riding is usually a better bet than being a construction worker, where pay often only comes on completion of a project and is sometimes withheld.

Technology under trial such as voice- controlled systems for riders may go some way to making their lives easier and safer. The companies are also experimenting with drone and robot delivery, but these automated options are unlikely to replace delivery riders within the next two to three years.

Waste Not, Want Not

The delivery business has created another problem which is annoying Chinese urban residents and causing headaches for urban administrators—more garbage. “China’s booming food delivery and e-commerce industries have resulted in a growing flood of plastic trash, with single-use food containers, plastic bags, spoons and disposable chopsticks clogging the country’s landfills,” says Yuan Cheng a campaigner with Greenpeace in Beijing. Greenpeace estimate that delivery by Meituan alone results in disposal of 60 million single-use plastic containers and cups a day.

“It’s pretty clear that an unnecessary number of plastic bags and packaging are used in food deliveries,” says Lena Turlaeva in Zhejiang, a province south of Shanghai, who orders meals from Ele.me two to three times a week. “The restaurants always include excessive amounts of disposable cutlery without even asking how many people the order will serve.”

Food hygiene issues have also been raised, with many of the food vendors providing food to the delivery companies found to the unlicensed. In the first half of 2018, Beijing Food and Drug Administration reported finding 20,000 illegal food vendors.

Second Thoughts

For now, the main strategy for the two main delivery operators in clawing their way toward profitability is the integration of more products into their operations, and despite the shaky financial model, both are likely to continue to grow because of the obvious market interest in the services they offer.

Alibaba has described Ele.me as a “local life services platform,” and Norris believes that is a strong indication that its services will extend well beyond food. “Given Meituan and Ele.me are starting to compete in a greater range of on-demand, lifestyle and localized services, these ‘super-apps’ have continued domestic growth prospects,” he says.

Despite the problems, these Chinese companies have created a business model that will survive and change eating habits everywhere. “China’s on-demand food delivery market is probably leading the world in a few respects: market scale, user uptake, market pervasiveness, service variety and payments integration” says Norris.